“What you think you will find is not what you find. That ought to be an axiom in archaeology.” (Ben Okri, FT Magazine October 19, 2018)

After decades of research had pinpointed Higgins Neuk as the likely location of a royal dockyard built by James 4th , hard evidence of medieval ship building has eluded us.

However, the four seasons of fieldwork have revealed some unexpected survivals that tell the story of the post –medieval landscape and the ingenuity and industry of the people who lived and worked here.

The site during excavation showing the main features we uncovered.

We knew from the historic maps and documents that mills used the water of the Pow Burn to power waterwheels since the 16th century.

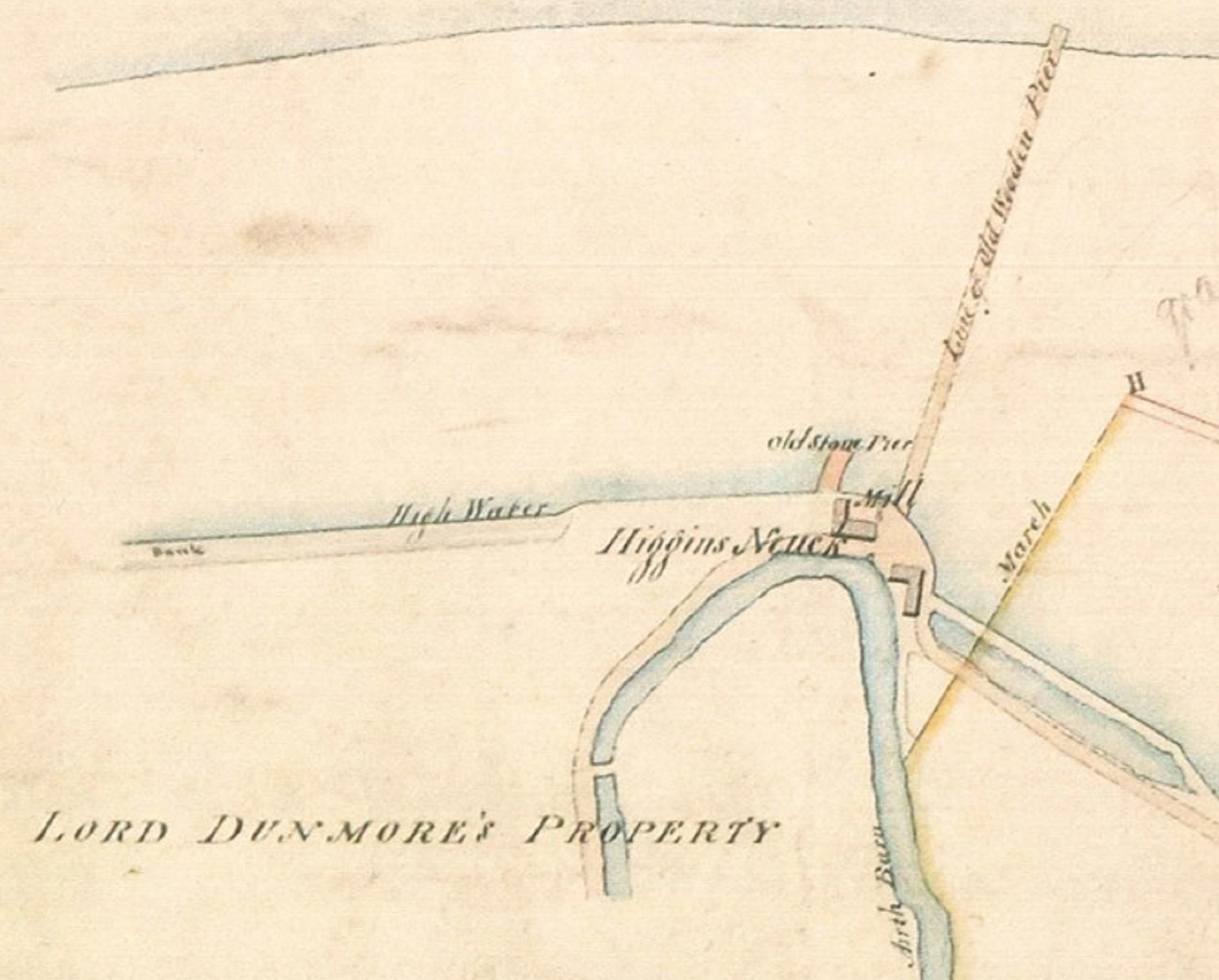

This map from 1828 shows two mills at Higgins Neuk and two old piers. Using the principle of working from the known to the unknown, we located our trenches on these features, as they might have been built on the site of the earlier dockyards.

To serve the mills, the course of the Pow Burn was engineered to create a millpond from a former oxbow by making a cut which isolated the bend.

The original course of the Pow Burn (left) and its engineered course for the mills (right).

A filled-in channel runs from the millpond through the middle of our trench to the site of the mill, and would have drained through a culvert in the sea wall into the Forth.

We think it may originally have been a natural channel which was later altered to become a mill lade. The gently sloping banks have been cut and faced with stone walls to contain the water and increase the flow to maximise the energy turning the waterwheel.

An overhead view of the mill lade channel showing the structures on the banks, including the iron and timber structure built into the stone retaining wall on the east side, which might be part of a sluice gate mechanism which controlled the flow of water.

Although the mill building itself has been almost completely destroyed, surviving hints suggest that it was built against one bank of this channel. Three stones form a pad or surface and a large foundation slab might be the side of a wheel pit, or a retaining wall for the edge of the lade. Deep deposits of chaff have built up here, showing that once this mill went out of use in the late 18th century, the redundant lade was used to dump waste from a second mill, which must have dramatically reduced the flow of water.

Prior to being ground, it was essential that the grain was perfectly dry and so corn-drying kilns are often associated with mills. This circular corn-drying kiln at Higgins Neuk is a great example.

The corn drying kiln seems to have been in use for a long time and was modified several times in the course of its working life.

The now collapsed drying floor was formed of malting bricks, large flat tiles perforated with small holes which allowed the hot air from the fire to circulate around the grain.

One of the malting bricks which formed the drying floor, with charred grain stuck to the bottom.

Mill complexes like this were intensively used, with constant maintenance required to keep the wheels turning.

One old millstone which had reached the end of its useful life for grinding was reused and laid upside down to form part of a paved yard or path leading from the road to the main mill building.

We knew from the excavation in autumn 2017 that the saltmarsh which forms the riverbank in front of the site had developed fairly rapidly through the 18th and 19th centuries, burying the stone pier and accumulating against the 3 metre-high stone sea wall which would originally have had tidal waters coming up to the face. Test pits also located the remains of the old wooden pier shown as obsolete on an 1828 map, which radiocarbon dating showed to be approximately the same age as the stone pier. These structures were probably associated with the Kincardine ferry that crossed the Forth from Higgins Neuk.

One of the earliest maps (dating to 1784) which shows the ferry crossing at Higgins Neuk, though it had already been active for hundreds of years by this time.

The ferry was first mentioned in Exchequer Rolls in 1330 but quickly suffered from silting up, prompting complaints from passengers as early as the 15th century. It wasn’t only foot passengers who struggled with wading through mud to get to the ferry boat, either – the importance of this crossing lay in its location on the main drove road from the Highlands to the Falkirk Tryst, the biggest cattle fair in Scotland from the 18th century.

A reconstruction drawing of the site showing what Higgins Neuk might have looked like in the heyday of the mill and the ferry which carried cattle over the forth at the end of the long journey to the Falkirk Tryst. (Credit: Inner Forth Landscape Initiative, Alan Braby)

By that time, the silting problem was becoming so acute that three different piers were built in a short time to maintain access to open water. The silting might have been exacerbated by the closure of the mill. When the lade was no longer needed to turn the waterwheel it was allowed to clog up with mud and chaff, so the flow of water through the channel and out to the riverbank would have slowed dramatically. The loss of its sluicing action flushing silt away from the sea wall and piers probably contributed to the eventual decision to move the ferry completely and construct a new pier to the east, ending the centuries-old association of Higgins Neuk with the river crossing.

The 1828 map shows the new pier for the Kincardine Ferry, located just to the east, as well as the old redundant piers at Higgins Neuk.

With so much engineering and construction on the riverfront here, it’s possible that any earlier activity associated with James 4th’s dockyard has been destroyed or buried. This is not to say that the remains of the docks don’t lie elsewhere in Higgins Neuk, awaiting discovery.

Some of the volunteers on site in May 2018.

However, thanks to the commitment and effort of a great many volunteers, together we have revealed a far more complex industrial and maritime landscape than we could ever have expected, supporting the archaeological axiom that what you think you will find is not what you find.

Recent Comments