One of the joys of coastal archaeology is that it encompasses sites of all types and periods. A recent recording visit to three stretches of the Solway coast with the Coastwise Project and local volunteers took us from remnants of Mesolithic forest to secretive D-Day preparations.

Solway Coastwise volunteers exploring and recording coastal archaeology

At Redkirk Point, where the river Esk meets the Solway Firth, a short stretch of coast tells the story of 8,000 years of a dramatically changing landscape. On the sloping bank, crumbling into the channel, tree roots, stumps and trunks embedded in the peat are the remains of mesolithic oak woodland, drowned by rising sea levels.

Tree stumps eroding out of the riverbank are the remains of 8,000 year old oak woodland

Land has been lost to the sea here in more recent history, too. The name Redkirk Point comes from a church (probably built out of the local red sandstone) that stood here since the 12th century. However, it too was overwhelmed as the land was washed away from beneath it in 1675. In the 1845 New Statistical Account, the local minister writes how:

“the tide and river whirling violently round that headland have swept them away entirely, but some old people yet remember the unwelcome sight of bones and coffins protruding from the banks…”

Mapping the line of the main channel from historic maps illustrates the constantly shifting nature of the Solway Firth waterscape.

The threat of loss to the sea here is perpetual, as illustrated by this timber structure which was recently uncovered by erosion not far from the site of the erstwhile Red Kirk.

Recent erosion has eaten away at the coast here, revealing this long wooden structure

Its purpose is unknown, but it may have been built in an effort to consolidate the eroding bank. Watch the Solway Coastwise film clip of our visit to Redkirk to get a sense of the river landscape here.

From the muddy shore of the Inner Solway Firth to the rocky coastline of Auchencairn, we explored how people in the past few centuries have exploited the potential of the carboniferous geology in this area. This is an extractive landscape of quarrying, mining and dashed hopes.

Coastwise volunteers at Auchencairn discussing the industrial history of the area

The description of this parish in the 1794 Old Statistical Account lists its many positive attributes, the only complaint being a lack of fuel. However, optimism shines through in a description of recent attempts to exploit coal seams exposed on the beaches…

“These lands lie upon the shore; and so promising are appearance that veins, 3 inches thick, of excellent coal, are found among the rocks at low water…”

A contemporary map by John Ainslie in 1797 also shows several coal pits along this coastline. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

We spotted a band of black shale that resembles coal in the coastal section at Auchencairn, and recorded the remains of several mine shafts in the hinterland. However, it seems the industry never progressed beyond the prospecting stage because late 19th century maps show only the ‘Old Coal Shafts’ of abandoned workings, while the New Statistical Account of 1845 is silent on the subject.

The 1895 2nd edition map shows a cluster of Old Coal Shafts – the mining attempt had been abandoned by then. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland

The short-lived interest in coal may have been the inspiration for companion industries such as salt production. A map of the Estate of Rascarrel from 1870 shows a salt pan on the beach, associated with several coal pits. We didn’t find any trace of the panhouse, however, an intertidal reservoir or bucket pot has been constructed using the natural shape of the bedrock with the addition of a stone wall. Seawater would have been pumped or bucketed from here to the salt pan.

A saltwater reservoir to hold back tidal water has been constructed using the natural shape of the rocky foreshore with the addition of an enclosing wall on one side to form a bucket pot

We also encountered evidence of two smithies built to service the mines. The first stands close to the salt works and is now almost completely disappeared. However, the layers being revealed as a result of coastal erosion contain smithing slag which confirms the building’s function.

Stone walling exposed in the eroding coast edge, while volunteers record the ruins of the smithy building beneath vegetation

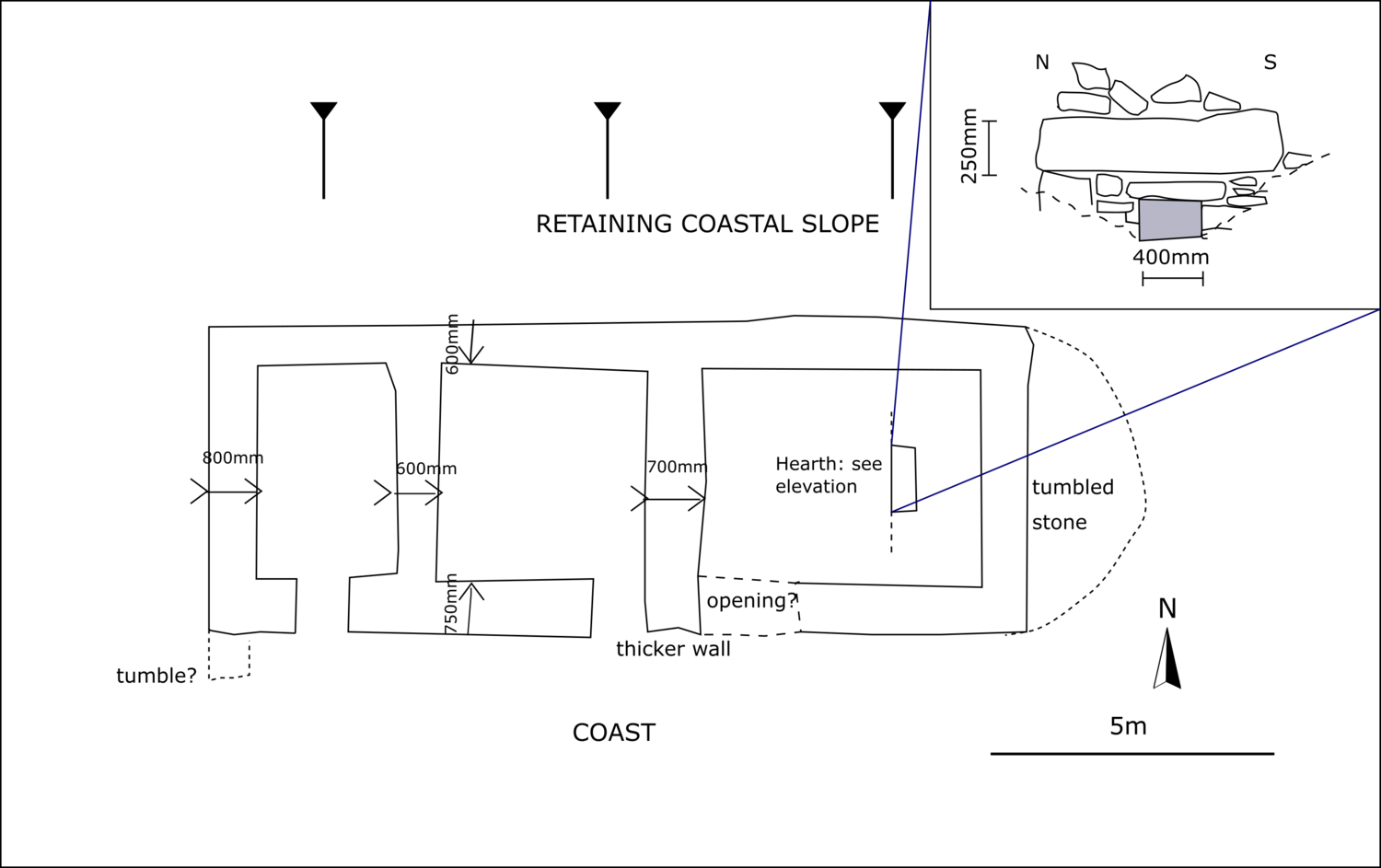

A later and better-preserved stone building to the east is known locally as ‘the smithy’, an identification confirmed by the discovery during our survey of a smithing hearth at one end.

A plan of the later smithy building showing the detail of the ironworking hearth discovered by volunteers on the east gable, which confirmed the building’s function.

Other minerals extracted at Auchencairn include barytes; a heavy white ore used in bleaching, and in the manufacture of paper and white paint. The mouth of a small mine tunnel on the shoulder of Little Airds Hill is marked by a scatter of the white barytes on the slope below. Nearby, a complex of buildings are the remains of a copper mine. We don’t have any records of its early history, but in the 19th century, the pump on which the workings relied failed, and the mine flooded.

The Coastwise group standing in front of the collapsed adit mouth which joined the copper mine.

The final attempt at exploiting the geology along this coast was in the 1950s, when a mining engineer named Billy Shaw reopened the old mine. Although primarily interested in investigating the barytes vein, they also encountered copper and quartz. However, the quality of the copper ore was too poor to be economically viable while the market for quartz (to supply pebbledash for the post-war housing boom) was dominated by companies from England. Recounting the history of the failed 1950s enterprise Shaw lamented the heavily faulted geology they encountered “so that little real sense could be made of it” and which precluded commercial success.

An unexpected surprise of a site – known locally, but not on historic environment records, was an intertidal quarry which worked the sandstone bedrock for millstones.

Lines of small holes forming circles on the surface of the intertidal rock show where wedges were driven in to remove circular slabs to be worked into millstones – these ones have been abandoned before they were extracted.

Here, the cavities left on the shore where large slabs have been removed attest to the quarrying activity, while lines of small holes along the bedding planes and forming circles on the surface show where wedges were driven in to remove slabs to be worked into millstones.

Our third stretch of coastline to investigate and record was Cairnhead Bay, the site of top-secret D-Day preparations. Watch the Coastwise film clip to see the site in its context.

Behind a rocky promontory on this secluded shore, you’ll be confronted by the unexpected sight of what appears to be a concrete boat.

It might be quiet now, but 75 years ago this coast was anything but. An essential element of the Normandy beach landings was portable harbours that could be secretly towed into position and used to land troops and supplies. This ambitious project, code-named ‘Mulberry’, required a pioneering engineering solution, which needed extensive testing. The stretch of the Wigtownshire coast around Garlieston was selected for its similar tidal range to Normandy, similar sea conditions, and its remote location to maintain secrecy.

Three designs were trialled here, and it was a storm at Cairnhead Bay that put them through their paces, leading to the decision to adopt the innovative floating roadway design that was ultimately successfully deployed on D-Day.

Wartime photos show the complete prototype harbour at Cairnhead being tested, helping us to understand the remains on site. Picture credit Imperial War Museum (IWM). From http://www.mulberryharbour.info/

Our concrete ‘boat’ is actually a ‘Beetle’, code-name for the pontoons that supported the floating roadway of the Mulberry Harbour that was used in Normandy. The Beetle is a rare reminder of the important role this remote section of the Solway coast played in Britain’s D-Day planning, but sitting on the beach and covered by the tide every day for 75 years it is also very vulnerable.

Visit the Garlieston Mulberry Harbour website to see contemporary photographs of the Mulberries at Cairnhead that explain the floating roadway and the role of Beetle pontoons in the construction, and then explore our 3-dimensional model of the Cairnhead Beetle to see what’s left of this ingenious design.

For much more detail of all our discoveries read the Solway Coastwise survey report.

Recent Comments